COVID-19 and Firearm Injury and Death

Rameesha Asif-Sattar

Project Policy Analyst,

The BulletPoints Project

The coronavirus pandemic has brought devastating socioeconomic impacts across the nation and with these, an increase in risk factors for firearm injury and death. We are seeing higher rates of anxiety, social isolation, substance use, suicide risk, and interpersonal violence, as well as a pandemic-fueled surge in firearm purchasing.1

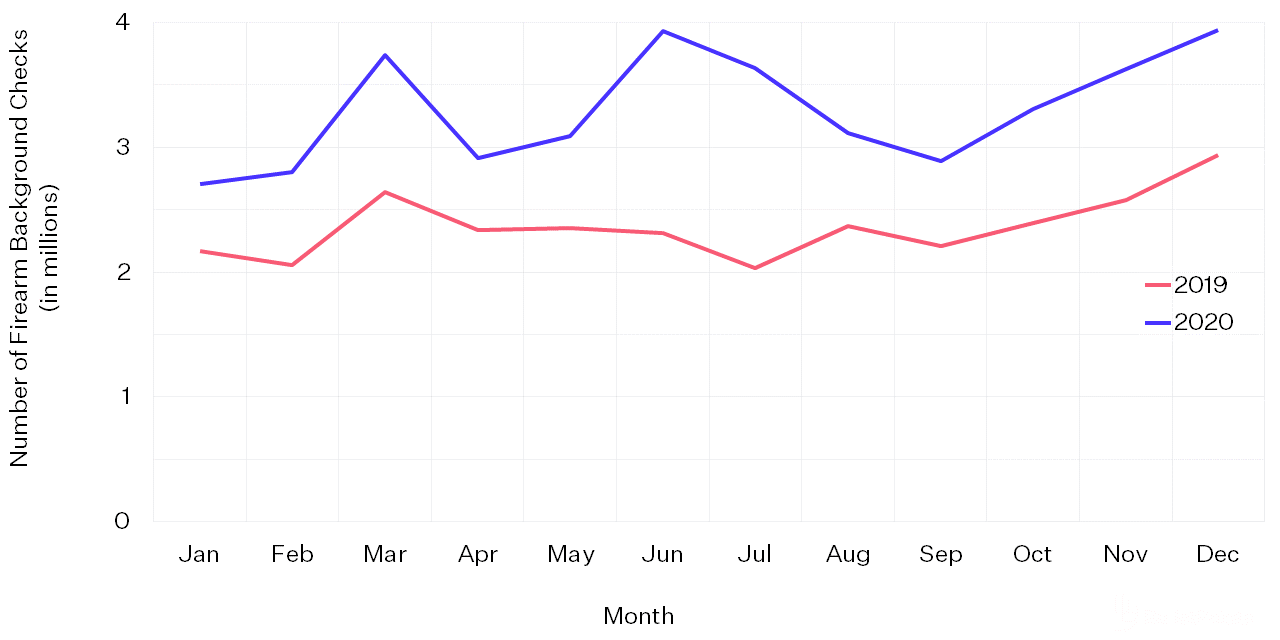

Between March and May of 2020, there were an estimated 2.1 million excess firearms purchased.2 Other proxy data indicates the increase continued through the year; the FBI conducted 40% more background checks in 2020 than in 2019, a record annual increase (Figure 1).3 Americans tend to purchase firearms in response to times of shock such as elections, natural disasters, and public mass shootings. Unfortunately, these spikes in purchasing are associated with increased injury and death.4,5

NICS Firearm Background Checks by Month, 2019-2020

According to a July 2020 survey among California adults, of those who acquired firearms, nearly half were new firearm owners.6 New owners may have less experience or training with firearms. Most people who acquired a firearm during the pandemic cited self-protection as the reason for doing so,7,8 with a particular worry for lawlessness, prisoner releases, government collapse, and government overreach during the pandemic.6 The majority of guns sold were handguns, which handgun owners own predominantly for self-protection.9,10 Additionally some firearm owners switched to less secure storage practices.6

In conditions of higher stress, the accessibility of a lethal weapon like a firearm increases the chance that a crisis or conflict leads to firearm-related injury or death.11

Suicide

Research suggests the pandemic has had adverse effects on Americans’ mental health. Isolation, fear, economic uncertainty, elevated stress, and increased alcohol use raise risk for suicide.11-16 This risk may be particularly elevated in individuals with pre-existing psychiatric conditions, those who reside in areas hard hit by COVID-19, those who have a family member or a friend who has died of COVID-19, and frontline healthcare workers.17 One in four adults, ages 18-24, reported seriously considering suicide during the pandemic.18 Another survey study found more than half of pandemic firearm purchasers had suicidal thoughts in the past year, and a quarter in the last month. These firearm purchasers with suicidal thoughts were also found to use less secure firearm storage habits.19

Suicide attempts are often impulsive responses to acute crises; sometimes only minutes pass between the decision to attempt and attempt.20 When a person with suicidal thoughts has access to firearms—the most lethal means of suicide—risk is further increased.21

Unintentional Injury

Fatal unintentional injuries reportedly surged in 2020: about 600 Americans died, an average 46% increase from prior years.22 This may be partially due to an increase in inexperienced gun owners.23 Estimates suggest that more than 2.5 million Americans became first-time gun owners during the first four months of 2020, and only 25% of those first-time buyers had taken some form of a firearms training course before purchase.24

Storing firearms loaded and/or not locked up may have also contributed. One survey found that 40% of new firearm owners who purchased a firearm in response to the pandemic report storing at least one firearm unlocked.8 In California, 55,000 firearm owners adopted a less secure gun storage method due to the pandemic. Half of these gun owners live with children and teens, who may be spending more time in the home and are at risk for unintentional firearm injuries.6

Interpersonal Firearm Violence

Research suggests the increase in firearm purchases in the first three months of the pandemic was associated with an 8% increase in interpersonal firearm violence in the US.2

Community Violence

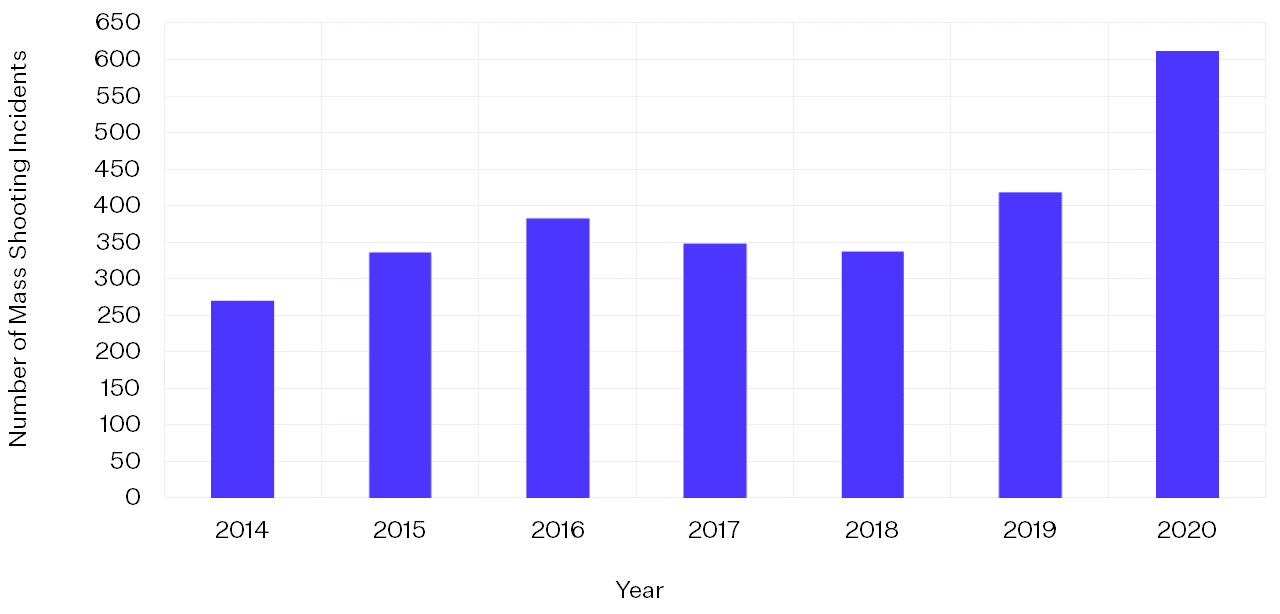

The pandemic has exacerbated the US’s unique firearm violence problem. In 2020, homicide rates rose by 30% from 2019.25 Mass shootings also exceeded any recent year by about 50% (Figure 2).22,26

Mass Shooting Incidents in the US, 2014-2020

In addition to increased access to firearms, upstream factors that play a role in the burden of gun violence in communities—poverty, unemployment, inadequate public services, and lack of educational opportunities—were worsened by the coronavirus pandemic.27-28 COVID-19 and its effects on social determinants of health have had a disproportionate impact on communities of color. Furthermore, the pandemic has strained violence intervention programs and community groups that proactively engage individuals and communities at risk for gun violence, further exacerbating conditions contributing to elevated homicide rates for communities of color.29

Domestic Violence

Shelter-in-place orders and amplified economic and interpersonal stressors have also elevated risk for domestic violence incidents, which increased by 8.1% following the issuing of stay-at-home orders.30 Experts suggest victims of domestic violence may be trapped with their abusers during the pandemic, therefore increasing the amount of control wielded by abusers and decreasing the ability of victims to access support from friends, family, and domestic violence resources.31 One survey of professionals who provide domestic violence support to victims found that 50% of the surveyed professionals reported an increase in abusers threatening to shoot victims since the start of the pandemic.32 An abuser’s access to a firearm increases the likelihood the intimate partner violence will become deadly by five-fold.33

What You Can Do

Right now, it’s important clinicians are cognizant of the fact that in combination with the pandemic’s socioemotional and economic effects, more people have guns in their homes than before. Furthermore, it is possible that more owners are keeping their guns stored loaded and unlocked, which may increase the chance that someone gets injured. These factors likely boost the risk for intentional and unintentional firearm injury and death.

Clinicians should assess for risk factors, talk with patients about risk and firearm access, and counsel on appropriate recommendations when indicated.

Clinicians should be aware that, when someone is suicidal, reducing access to lethal means can save lives. Knowing about safe firearm storage and temporary transfers can help. In times of more acute risk, involuntary measures like an emergency psychiatric hold or a gun violence restraining order (GVRO) may be merited. For reducing unintentional injury, safe firearm storage that makes guns inaccessible to children and others at risk is critical. Clinicians should screen patients for domestic violence, including asking about the presence of firearms in the home or if the abuser has access to firearms. In addition to screening, clinicians should be aware that domestic violence restraining orders (DVROs) may help to protect patients from intimate partner violence.

Clinicians can consider advising owners, especially new owners, to get formal training in safe firearm handling and storage practices to reduce the risk of fatal and nonfatal unintentional injuries.

I hope these insights help you, as a clinician, become a more informed and effective partner in keeping your patients safe and in reducing the overall burden of firearm injuries and death.

Clinical tools for preventing firearm injury

- U.S. firearms sales: March 2020 unit sales show anticipated COVID-19-related boom.

- Firearm purchasing and firearm violence in the first months of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States. MedRxiv.

- NICS firearm background checks: day/month/year.

- The impact of spikes in handgun acquisitions on firearm-related harms. Injury Epidemiology.

- Firearms and accidental deaths: Evidence from the aftermath of the Sandy Hook school shooting. Science.

- Public concern about violence, firearms, and the COVID-19 pandemic in California. JAMA Network Open.

- Threat perceptions and the intention to acquire firearms. Journal of Psychiatric Research.

- Firearm purchasing and storage during the COVID-19 pandemic. Injury Prevention: journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention.

- U.S. firearms sales December 2020: sales increases slowing down, year’s total sales clock in at 23 million units.

- Firearm ownership and acquisition in California: Findings from the 2018 California Safety and Well-being Survey. Injury Prevention.

- The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine.

- Rebalancing the ‘COVID-19 effect’ on alcohol sales.

- Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Network Open.

- The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review.

- A closer look at substance use and suicide. Resident’s Journal: journal of the American Journal of Psychiatry.

- Is the pandemic sparking suicide? The New York Times.

- Meeting the mental health challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatric Times.

- Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, June 24–30, 2020. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

- Suicidal ideation among individuals who have purchased firearms during COVID-19. American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

- Characteristics of impulsive suicide attempts and attempters. Suicide & Life-threatening Behavior.

- Suicide acts in 8 states: incidence and case fatality rates by demographics and method. American Journal of Public Health.

- https://www.gunviolencearchive.org

- Coronavirus fears have produced a lot of new gun owners – and safety concerns. NPR.

- Millions of first-time gun buyers during COVID-19. NSSF.

- Pandemic, social unrest, and crime in U.S. cities. The Council on Criminal Justice.

- https://www.gunviolencearchive.org/methodology

- Social capital, income inequality, and firearm violent crime. Social Science & Medicine.

- Engaging communities in reducing gun violence: a road map for safer communities. Urban Institute.

- Violence interruption goes remote thanks to coronavirus restrictions. WAMU.

- Domestic violence during COVID-19. The Council on Criminal Justice.

- Why a drop in domestic violence reports might not be a good sign. The New York Times.

- Assessing challenges, needs, and innovations of gender-based violence services during the COVID-19 pandemic: results summary report. National Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

- Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: results from a multisite case control study. American Journal of Public Health.